Choice in shale frac’ing is alive and well, but the last few years of pricing pressure have caused pressure pumpers to vigorously innovate, compete and consolidate. This has helped them to weather the latest oil pricing cycle. Now, it’s the turn for their Exploration & Production (E&P) company customers to follow suit. Let’s dive into what got us there and why I think E&Ps are next.

Some of Our Best Work Is Done Horizontally

The frac industry goes back to the late 1940s. For many decades, frac targeted “conventional” rock, rock with a modest to high permeability and with accumulated oil and gas resources, through vertical wells that were frac’ed with a single frac job, or maybe multiple isolated jobs that were targeting different geologic horizons at different depths. The initial shale fracs, done in the late 1990s and targeting the oil & gas source rock with permeabilities that were 3-6 orders of magnitude lower than these conventional rocks, were also done in vertical wells. Up to that time, horizontal wells were generally only used for extended reach from a single (offshore) location, or to economically wrap up relatively thin stranded oil & gas resources at the edge of a reservoir. That changed with shale, the “unconventional” rock, when it was discovered that the creation of fracture surface area was critical to its economic success.

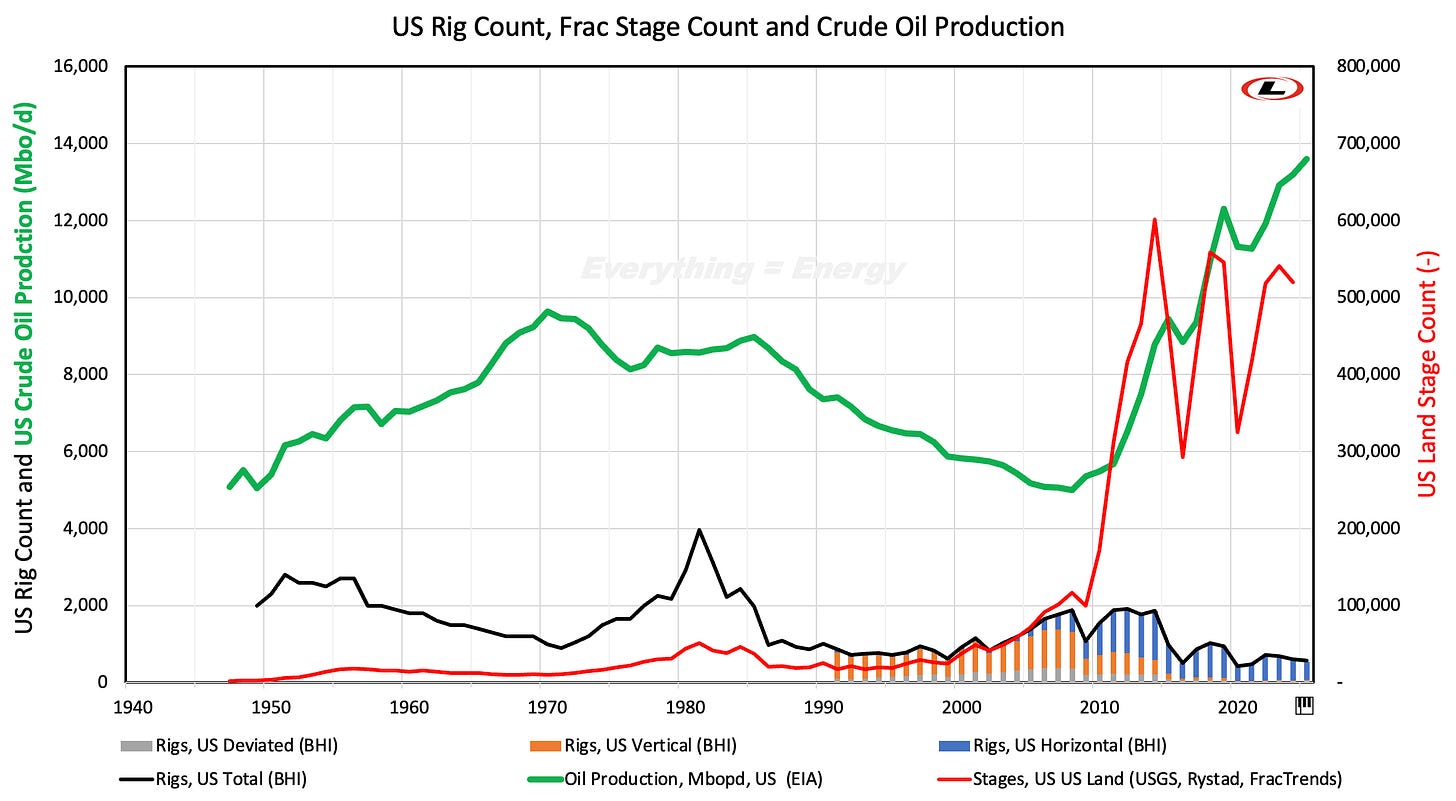

As shown in Figure 1, this focus on fracture surface area creation in the shale reservoir has a two-prong implementation approach: horizontal drilling and multi-stage frac’ing.

Everything = Energy supports the Bettering Human Lives Foundation. Consider becoming a paid subscriber to support clean cooking for African families

When Mitchell Energy found it was possible to produce natural gas directly from the shale source rock using high-volume slickwater frac jobs, they did so from vertical wells. Devon Energy, after purchasing Mitchell in 2002, quickly turned the Barnett Play “horizontal” – meaning, that they would only drill horizontal laterals through the Barnett source rock and combine it with Mitchell’s slickwater design fracs in a multi-stage fashion, just repeating Mitchell’s vertical well frac process a few times along the horizontal lateral.

Between 2005 and 2015 the entire industry essentially went from vertical to horizontal drilling. “Some of my best work was done horizontally”, as originally quoted by Mae West, ended up a valuable lesson for the shale industry.

Figure 1: Rig count (in black), frac stage count (in red) and US crude oil production (in green) from 1949 – 2025. Vertical rig count is colored in orange and horizontal rig count is colored in blue (since BHI started tracking it in 1991).

But horizontal drilling by itself was not sufficient. The second prong for the Shale Revolution was multi-stage frac’ing. This reflects the ability to isolate a section of the horizontal lateral to conduct a frac job, often called a “frac stage”, to treat that portion of the lateral just as if it was a single frac stage in a vertical well.

Conduct a few frac stages as if they were frac’ing a few vertical wells, placed within a few hundred feet from each other, in separate fracture treatments. In sequence, they would set a plug to isolate the new zone to frac with the previous zone, perforate the new zone, and then frac it. Then, rinse and repeat maybe a handful of times, but now on average almost 50 times along the same lateral. In this process, frac crew gradually works it way from the “toe” of the horizontal well, the farthest point along the well, toward the “heel” of the well, the point of the lateral nearest to the vertical section of the well. Frac’ing multiple times from different positions along the horizontal lateral simply “stacks” a number of vertical-well frac designs right next to each other. Think of it as a loaf of bread (the entire fractured area along a lateral) as created by the sum of stacked slices.

Figure 1 shows also that for many decades, vertical wells in the US were frac’ed at a steady pace of about 25,000 frac jobs / stages on a yearly basis. This pace accelerated temporarily following the Arabian Oil embargo in the early 1970s, with a renewed focus on tight gas and the discovery and development of Alaskan oil. Then came the oil bust of the 1980s and a gradual decline in US oil production. With the introduction of horizontal drilling along shales, staging increased by about 20x, from ~25,000 stages/year to the current plateau ~500,000 frac stages/year.

There is an economic advancement to drill and frac from a single horizontal well instead of a few vertical wells. Let’s do some rough math. Let’s assume it costs one unit to drill and one unit to frac a well. Now, instead of creating a few redundant vertical wells five times – let’s drill that vertical section just once to create a pathway for hydrocarbons to be brought from the reservoir to the surface. This saves you from drilling four vertical wells. Drilling the horizontal lateral is more expensive – let’s assume twice as costly as a vertical. On the frac side, very little changes, as five separate frac jobs have to be conducted. There will be a slight cost increase to enable multi-staging, but the additional cost is negligible. To frac and drill 5 separate well cost 10 units; to drill a horizontal with 5 frac stages costs about 7 units. So, with some quick math: same production, but about 30% cheaper with one multi-stage horizontal well.

The above was the crude math more than a decade ago. Today, where stage intensity allows us to go up to an equivalent of one hundred vertical wells, and where lateral drilling has become cheap, the choice of a horizontal well is significantly more advantaged and has become a no brainer.

Even if the production per unit area is tiny, there is so much area created that the combined production from all these areas is significant. In some modeling exercises, it has been shown that the fracture surface area in a modern frac’ed unconventional well is at least 100x larger than a past conventional frac job, and possibly 1,000 – 10,000x larger than an unfrac’ed well. Even if a square foot tile of fracture surface area only produces a teaspoon of oil every day, in a shale well with millions of square feet of surface area that can easily amount to 100 barrels of oil per day (bopd) – a typical production of a shale well that has been producing for a few years.

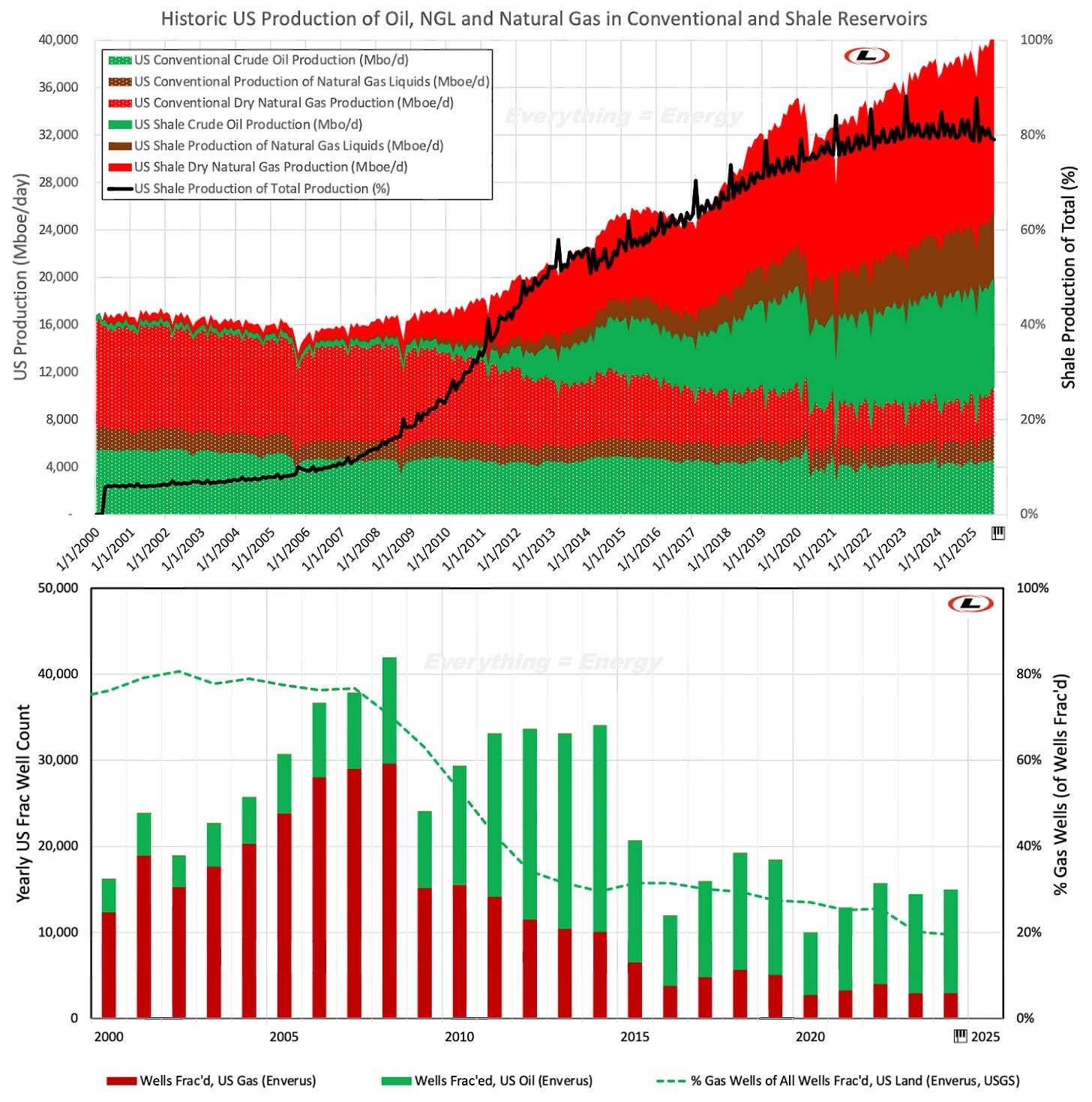

While stage intensity per well increased over the last decade, total well count per year dropped while US production was still breaking daily records. As shown in Figure 2, conventional oil, NGL and natural gas production has continued to decline, but oil, NGL and natural gas from shale has kept growing and now marks about 80% of all US oil & gas production.

While most wells are targeted for the crude oil, dry natural gas wells only represent about 20% of the entire US Lower 48 well count. Still, most of the US equivalent energy production is from natural gas. While some of the natural gas we produce is associated gas tied to the production of crude oil, some basins such as the Marcellus and the Haynesville only produce dry gas. It is these basins where most of our primary energy is produced – but that’s a story for another time.

Figure 2: (top) Daily US production of crude oil, natural gas liquids and dry natural gas, as produced from conventional and unconventional rock; (bottom) yearly frac well count Frac well count an Frac crew count 2000 – 2025. Note that natural gas well count only represents 20% of the total well count.

Intensifying Fracs

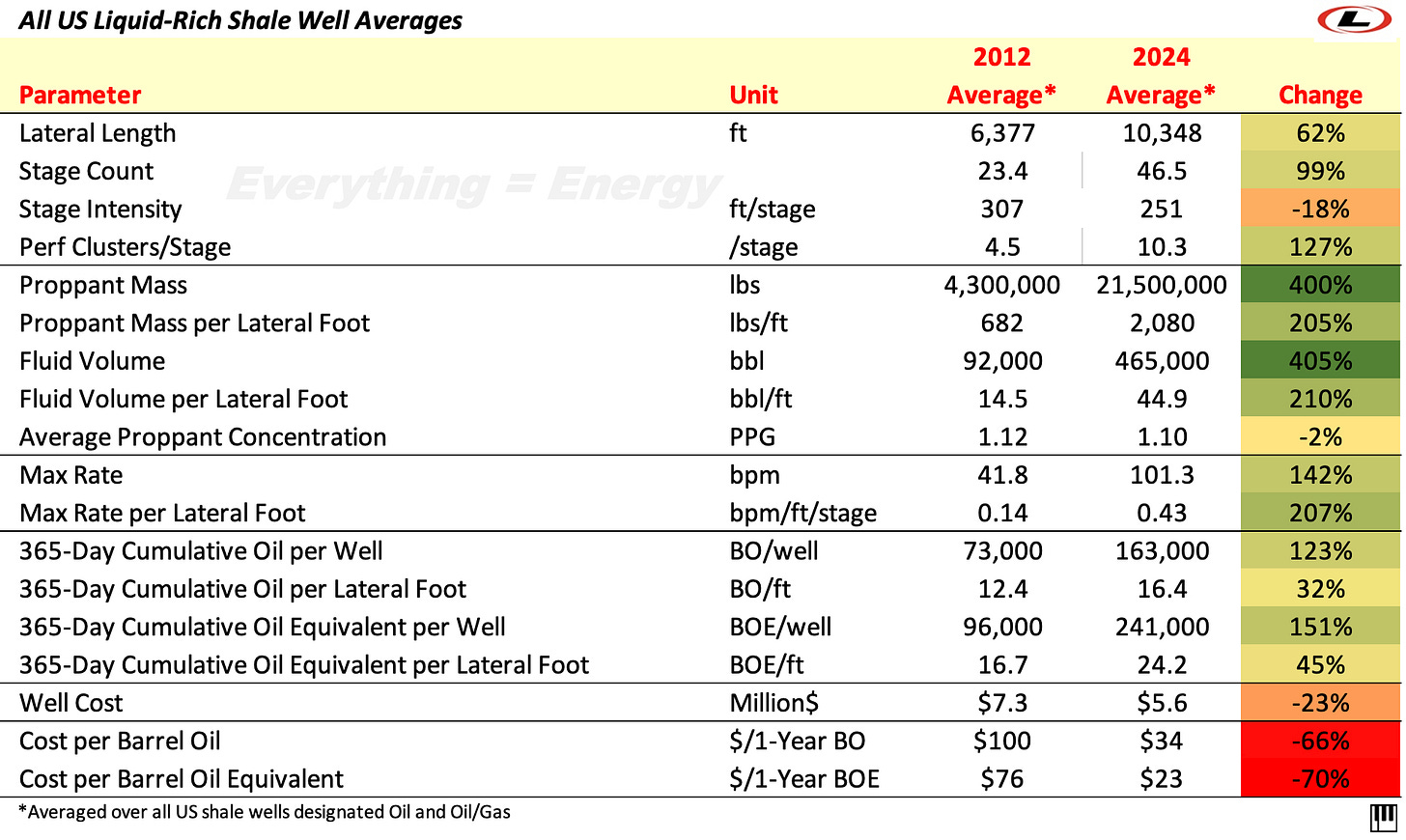

While US stage count has increased, and also has increase on a per-well basis, other parameters that define a frac job have scaled with that stage count per well. A summary of that increase in various intensities to treat a well is provided in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Increased frac requirements by well between 2012 and 2024.

As we discussed before, pursuit of propped fracture fracture surface is the main goal, as it connects a well with long-term access to more oil and gas trapped in shale. The intensification of fracture treatments is done through increasing areal extent and fracture density. There are five big-picture intensities the industry has been tweaking over the last decade:

- Stage intensity

- Cluster intensity

- Injection rate intensity

- Fluid volume intensity

- Proppant mass intensity

The ultimate consequence of all these changes is that oil, natural gas production increases in the first year and over the lifetime of a well. While these intensities all increased, they paradoxically also led to a reduction in the drilling and completion cost of a typical well.

Let’s get this straight from Table 1 – on a per-well basis, stage count doubled, perf clusters more than quadrupled, proppant mass and fluid pumped per well increased 5x, injection rate increased 2.5x, resulting in a 2.5x increase in barrels oil equivalent production, (365-day production) while shale well cost dropped by 23%!? On a per barrel-oil-equivalent production basis, that is a 70% cost reduction.

These cost saving are for the E&P company, the company that took the risk to develop an asset with a fluctuating price. But these savings have only been possible and sustainable through the work of drillers, pressure pumpers and other oil & gas well service providers. For them, delivering these gains has only been possible as they benefit from their own efficiencies.

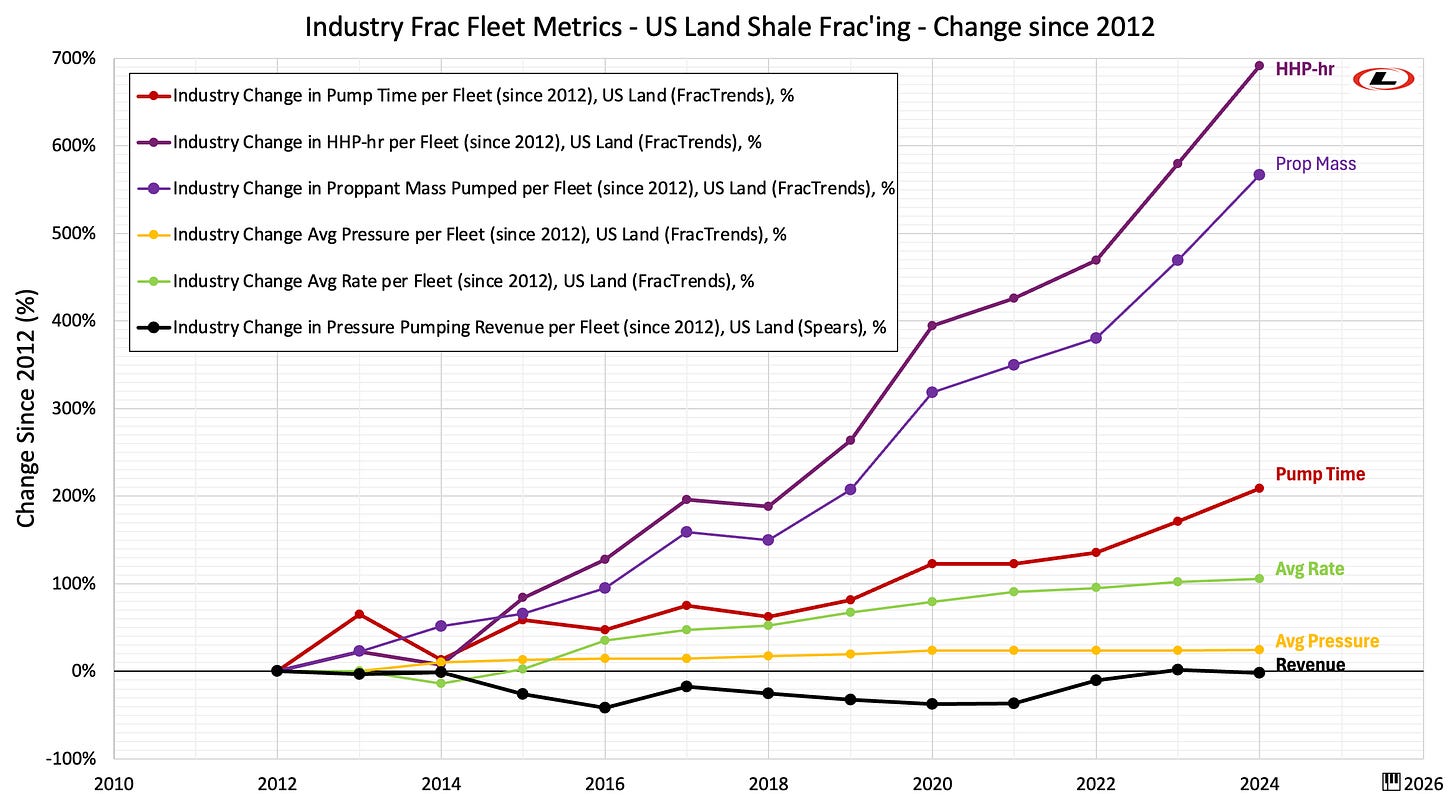

Figure 3 below shows the achieved efficiency and throughput gains by pressure pumpers, as calculated by individual frac crews. On a yearly basis, a dedicated frac crew today is doing substantially more work than 12 years ago, but it earns the pressure pumper about the same amount of revenue.

Frac crews pump against a surface pressure that is on average 25% higher than before (mostly because they pump faster and have to overcome more friction), pump at more than double the average injection rate, and have increased their daily pump time by 3x (from less than 20% of every day of the year to more than 50%).

The product of pump time, pressure and rate is work, which has increased 8x, while proppant throughput is up almost 7x. It should be noted that this frac crew in 2024 is not quite the same as what it was in 2012 – it has about double the equipment and associated hydraulic horsepower available to it. While frac crew count has been cut by about half in 12 years, somewhat mimicking the reduction in rig count, frac equipment horsepower has barely changed as it has been redistributed over fewer crews.

Figure 3: Various changes by frac crew, as expressed in %change since 2012.

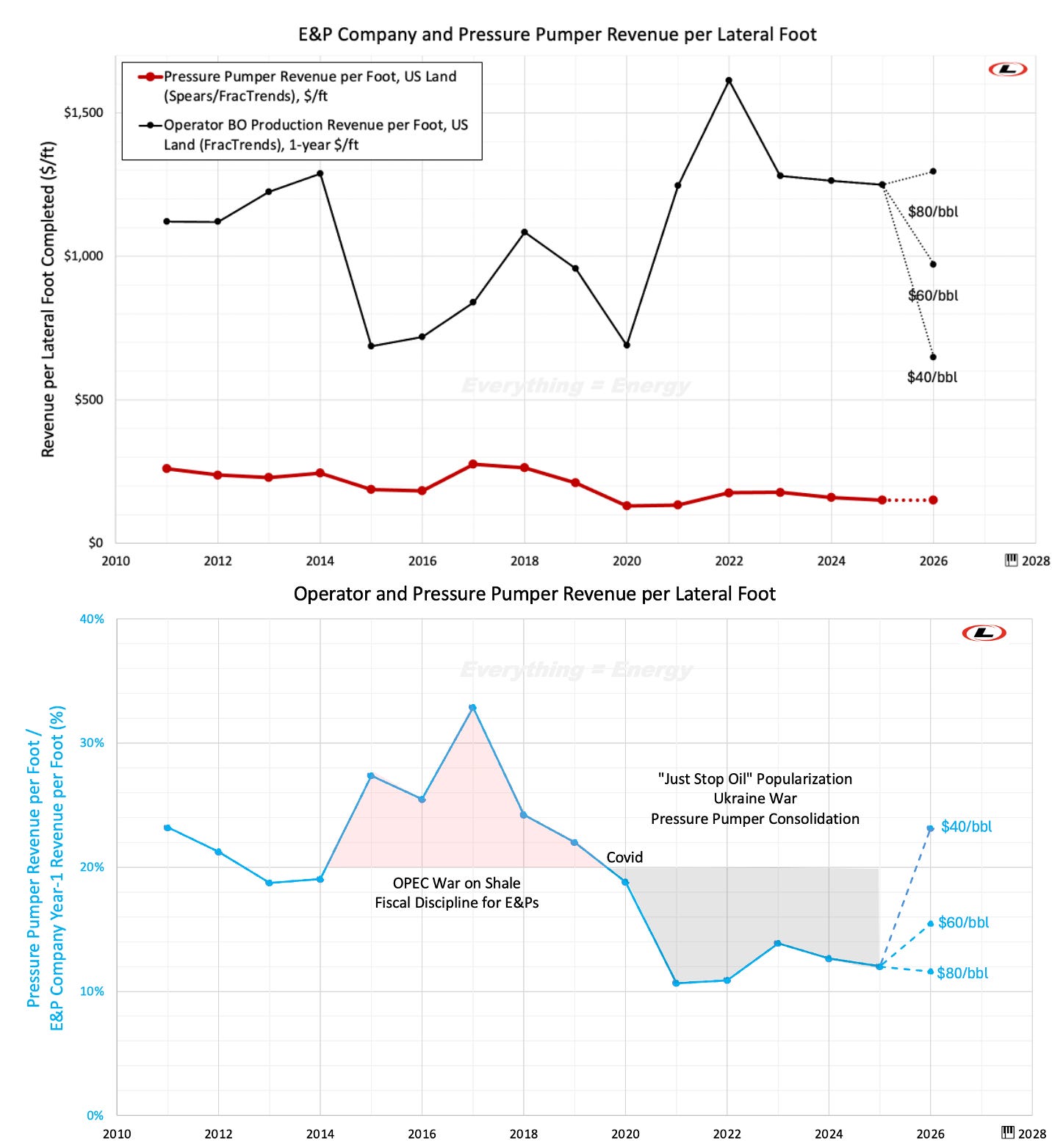

There are few metrics where it is possible to directly compare performance of E&P and pressure pumpers. Pressure pumpers often look at pounds of proppant placed, total pump time or pumped volume, but we can also break down their performance on a per lateral foot basis along the horizontal. Lateral footage can also be a metric associated with production normalization, and as such we have a means to compare revenue performance of pressure pumpers and E&P companies.

Forced into Fiscal Discipline

Figure 4 shows the revenue evolution for a pressure pumper associated with frac’ing a foot of a lateral. That revenue has gradually receded, from about $240/ft to $160/ft, even as pressure pumpers have crammed 4x more material and about 5x more HHP-hrs of work within that lateral foot.

The E&P is the risk taker, with the potential upside that the barrels of oil they produce fetch a good price on world markets. In my calculation of revenue, I am simplifying the revenue gained by the E&P as just the revenue associated with only the first year of production. In general, a shale well’s estimated ultimate recovery (EUR) is expected to be about 6x the first year’s production, but I have ignored the contribution from these later years here.

In the early years of the Shale Revolution, E&Ps would fetch more than $100 for a barrel of their oil. The focus was on growth, almost at any cost, and as a result pressure pumpers got volume. In these early years, average oil production in the first year was about 12 bo/ft, and therefore the revenue per foot is in the $1,200/ft range through 2014.

“I expect further E&P consolidation to be driven by scale advantages to further lower well and per-barrel cost…”

However, this boom lasted until about Thanksgiving of 2014, when Saudi Arabia declared war on shale, and WTI prices slumped to ~$50/bbl. This was the incentive operators needed to improve, and their production quickly increase to about 18 barrels of oil per foot (bo/ft), where this metric peaked around 2021. It currently sits around 16-17 bo/ft. Of course, pressure pumpers reduced the pricing of their services, but the impact of dramatically lower oil prices had a bigger impact for E&Ps. They learned the hard way – no more frivolous growth at all cost, cut cost, focus on cash flow and investor returns. It was a return to fiscal discipline that reminiscent of the dot-com bust.

With COVID and the associated government response, pressure pumpers caught up with the lower oil prices. But fairly quickly after 2020, oil prices recovered, partially due to Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine, partially due to the popularization of the Just Stop Oil movement in western governments that put limits on oil supplies without trimming demand. Higher prices for its products, as well as the rewards of fiscal discipline, have ensured that E&PS have been at a pricing advantage since 2021.

Figure 4: (top) pressure pumper and E&P company revenue associated with the completion and production of 1 foot of the lateral; (Bottom) Pressure pumper vs E&P approximate earnings per ft of lateral completed. Note that E&P company earning are calculated from year 1 production per foot and multiplied by the average WTI oil price that year.

This financial squeeze on pressure pumpers has had consequences. The boom days of the early 2010s, where more than 70 pressure pumpers existed, are over. Many did not survive OPECs 2014-2016 war on shale or the governments extended COVID response. While some companies did not survive, their assets were bought by competitors for pennies on the dollar and were consolidated by fewer competitors.

My expectation is that 2026 will swing back to a more balanced revenue comparison between pressure pumpers and E&Ps. Pressure pumpers have lived in an environment that feels like $45/bbl oil prices for many years, and it is unlikely that actual prices will drop that low.

Forced into Consolidation

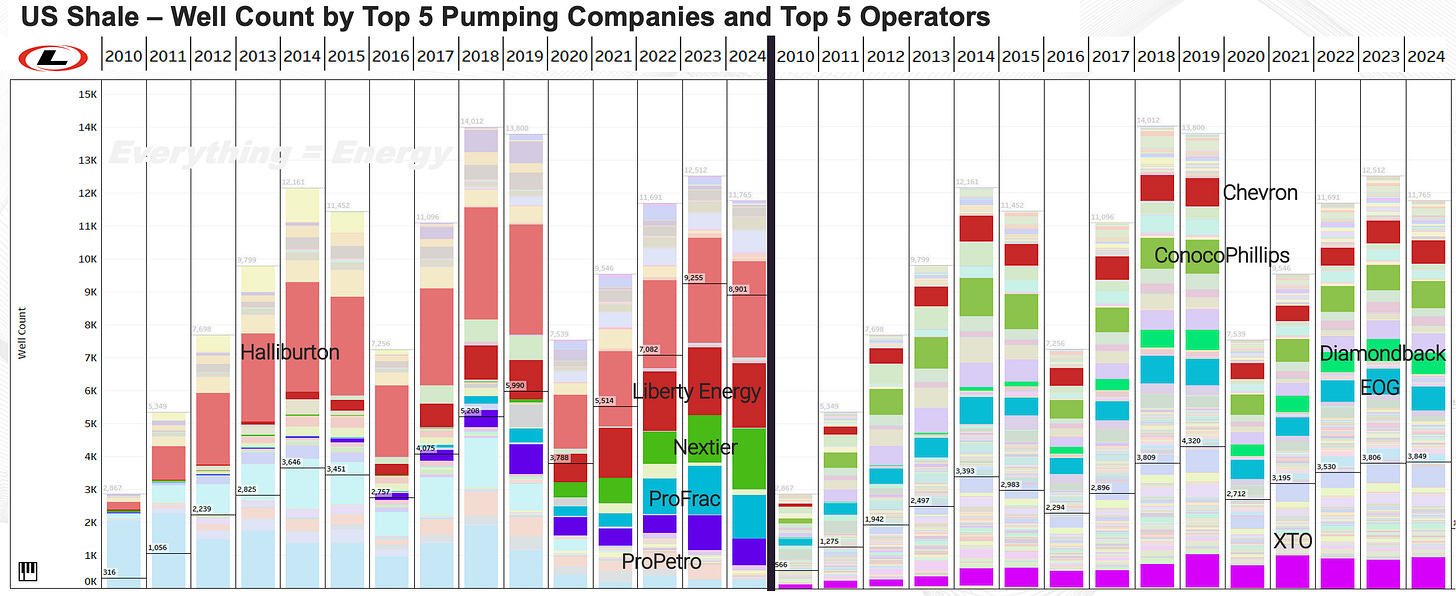

Figure 5 shows US Shale Well count by year, as highlighted by the current top 5 (by well count) pressure pumpers and top 5 E&P companies. The top 5 pressure pumpers have a market share in well count of about 75% (up from 30% in 2012), whereas the top 5 well share for E&P has not changed very much since then and stands at a little over 30%.

Halliburton is the only big pre-shale pumper that still works in the US, where it has maintained its position as the biggest pressure pumper for now. Liberty Energy, Nextier, ProFrac and ProPetro have all consolidated other pressure pumper businesses within them and grown into fierce competitors with the legacy pumper.

Amongst E&P companies, XTO, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Diamondback and EOG are the top 5 US frac’rs, and their combined yearly frac well count stands at 3,800 wells, or about 32% of US frac well count. In my view, this shows one of the strengths of the Shale Revolution and its American origin – the depth of this operator market is second to none. This allows room for some crazy experimentation that, if successful and in due time, can and will be adopted by others.

Figure 5: Top 5 E&P and pressure pumper company well count (2010-2024).

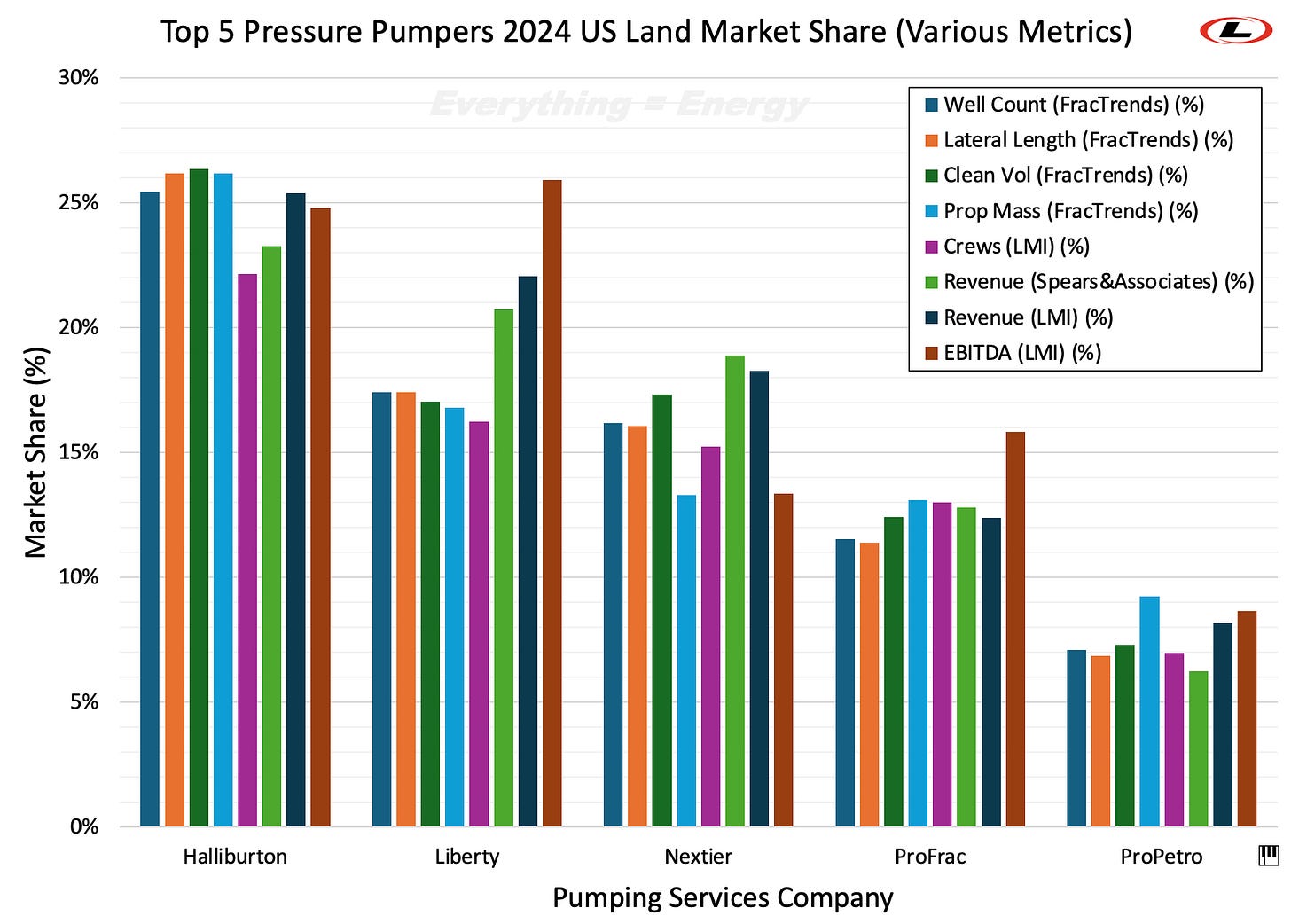

Figure 6 shows a few other market share metrics for the top 5 pressure pumpers, as reported through FracTrends, Spears&Associates and Liberty Market Intelligence (LMI).

Most big pressure pumpers show efficiency in operations. This is visible through the appearance of a lower market share for crew count than for various other throughput metrics. For example, Liberty Energy’s crew count market share is at 16% (in dark pink), but it fracs 17% of all US wells (in dark blue). That means it has effective crews that swing above their weight in operational efficiency.

The bar diagram also shows that most of these bigger pressure pumpers are fiscally efficient. While they combine for about 75% of the US frac well count, they account for more than 85% of industry revenue, and almost 90% of the industry’s combined EBITDA in 2024.

Figure 6: Top 5 pressure pumper market share metrics for various frac and capital efficiencies (2024).

These pressure pumpers have allowed for the adoption of simulfrac, are running most of the pumps on cheap natural gas instead of diesel, and have implemented machine learning (and AI) to automate responses to thousands of edge devices that inform of equipment health while orchestrating the best combination of pump settings for the given circumstances to do a frac job in the most economical manner. They have mastered mine-to-well logistics that come with moving millions of tons of sand, and they have made sand delivery quieter and cleaner than ever before. They have upgraded every piece of equipment on their modernized frac locations to obtain a smaller footprint and become a better neighbor.

These companies are innovation machines that have taken the best of their melting pots of technical know-how and cultures. Over the last few years, several of these top pressure pumpers have re-enacted the fiscal discipline achieved by E&Ps a few years before them. Most of them have not been tempted by the “growth at all cost” mantra that served our industry so poorly in the early shale boom years.

Thanks for reading Everything = Energy! Please help spread the word and …

With oil prices toward the lower end of the cyclical spectrum, my expectation is that it is now E&Ps turn to further consolidate. Change is the only constant in the oil field, and I think there will be more consolidation on both sides, but in the near future meaningful consolidation is more likely to happen amongst E&Ps.

I expect further E&P consolidation to be driven by scale advantages to further lower well and per-barrel cost, especially associated with (1) Adoption of simul-, trimul- and quattrofrac operations; (2) Large surface locations (“monster pads”) with more wells per pad as a semi-permanent of a frac crew will further help to decrease time dedicated for rig down, rig up and moves; and, (3) Rotating scheduled pump maintenance through temporarily inactive pods while the remaining rigged-in equipment delivers continuous 24/7 pressure pumping, albeit at the cost of some prudent equipment redundancy, and assuring that well planning and logistics keep up with these step-changes in frac’ing.

Pressure pumpers have scaled up to achieve these tasks in the years ahead. The E&Ps should be able to drive their cost advantages through upscaling and pursue smaller players who cannot implement this into their operations.

Conclusions

- The US production boom has been driven by a pursuit of fracture surface area

- Frac stages are the simplest metric for the frac intensity increase associated with this surface area increase

- The cost to produce a barrel of oil from shale is down about 70% since 2012. This has given North American shale barrels leverage toward lower oil prices.

- Financially, E&Ps were first hit hard following OPECs war on shale in 2015-2016. During the last few years, however, pressure pumpers and other service companies have been hit hardest by lower prices for their services.

- As a result, pressure pumpers have worked hard to adopt innovations, and they have also consolidated more than E&Ps. Today, about 85% of all frac-related revenue comes from just 5 pressure pumpers.